- The Awards

- History

AN POST BOOKSHOP OF THE YEAR

Read about the newest award to be added to the An Post Irish Book Awards

- Media Centre

- Resources

Menu

Read about the newest award to be added to the An Post Irish Book Awards

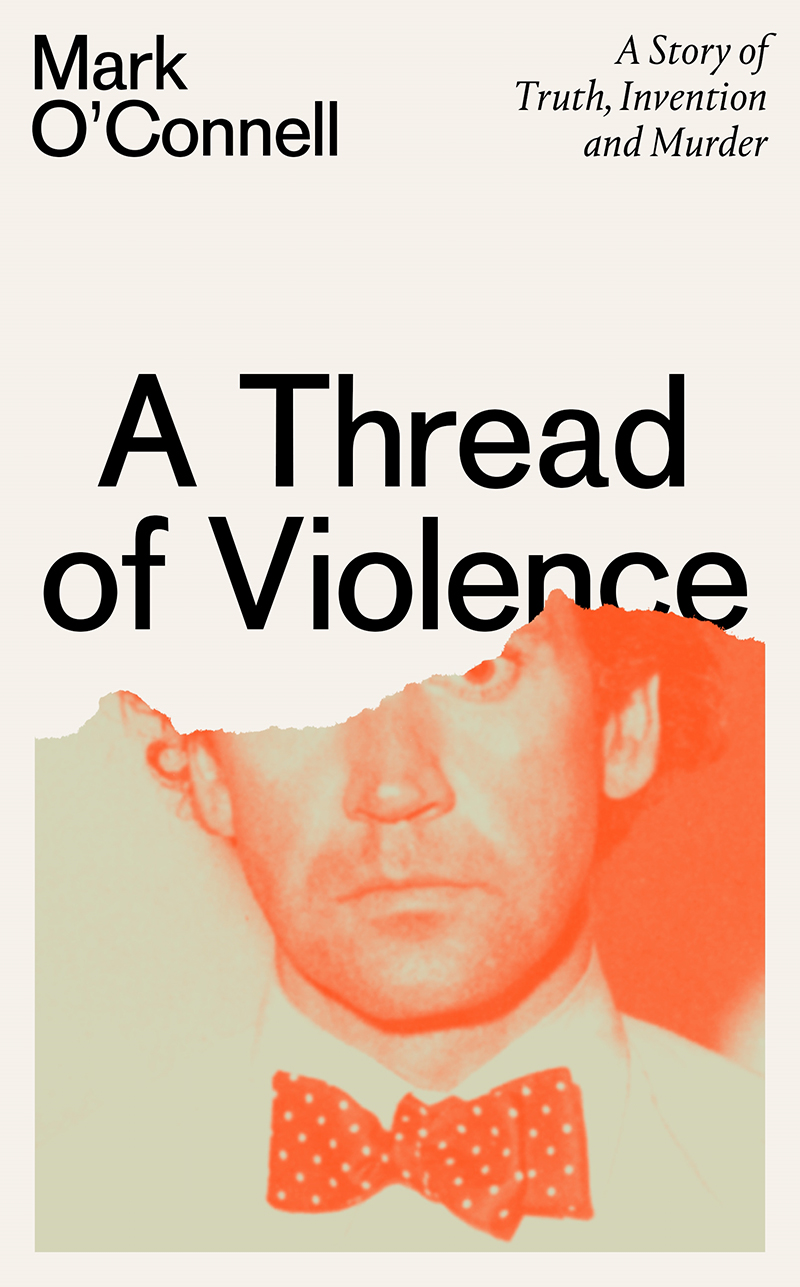

Mark O’Connell is an award-winning Irish writer; his first book, To Be a Machine, won the 2018 Wellcome Book Prize and was shortlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize, and in 2019, he became the first ever non-fiction writer to win the prestigious Rooney Prize for Irish Literature. He is a contributor to the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker. His latest book, A Thread of Violence, is a confrontation of true crime, a negotiation with the act of writing about murder, and a navigation of the chasm and interplay between fiction and non-fiction, taking the infamous case of Malcolm Macarthur as its subject. A Thread of Violence is shortlisted for the Dubray Non-Fiction Book of the Year. (Photo credit: Fergal Phillips.)

Congratulations on making the shortlist for the Dubray Non-Fiction Book of the Year Award! How does it feel?

I’m very honoured to be shortlisted.

Tell us a bit about your shortlisted work?

A Thread of Violence is a book about the murders committed by Malcolm Macarthur in 1982, and the long aftermath of those crimes. It’s an attempt to reckon with the roots of violence, and with the morality of writing about it. It’s also, fundamentally, a book about the relationship between a writer and a subject, and about the fundamental unknowability of other minds.

What drove you to write this book?

So many things brought me to this subject. My grandparents lived in the same apartment complex that Macarthur was arrested in, so I grew up hearing about it. I also did a PhD on the work of John Banville, whose novel The Book of Evidence was loosely based on MacArthur’s crimes. So I encountered Macarthur first as a fiction, and the book is deeply concerned with the relationship between fiction and non-fiction narrative. This is something that has always fascinated me, and which drew me into this subject.

What was the research and investigative process like of putting together the book?

I spent several months researching the story in archives before I met Macarthur, and then perhaps two years speaking to him about his life and the murders. It was often difficult, often frustrating and confounding, but never less than fascinating.

What was the emotional impact of writing it like?

Deeply complex. I was often very conflicted about what I was doing, about the morality of writing about these horrible murders, and the approach I took. All of that difficulty is part of the book itself, and so the emotional impact of writing the book is in a way a subject of the book.

How did you navigate the distance between yourself and your subject? Or alternatively, how did they become intertwined?

I spent more time with Macarthur than I have ever done with a subject before, and so the relationship became very complicated and fraught. There was an intensity to it that was beyond what I’d experienced before. In part, I navigated the distance through trying to spend as much time as possible coming to know him, and to understand what his motivations might have been. What I found myself ultimately navigating, though, was the distance between Macarthur and the facts of his own life.

What is next for you? Is there anything pulling at your attention?

I wish I knew! I’ll figure it out, but right now I’m just working on shorter projects, and collaborating with other artists.

What An Post Irish Book Awards shortlisted book is next on your to-be-read pile?

I’m looking forward to reading Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song, which I have heard such great things about.

Explore the Dubray Non-Fiction Book of the Year Shortlist here.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |